What if the “Old Paths” Are Actually New? (Part 2)

In Part 1, we discussed if the “old paths” are actually new.

Now, in Part 2, we will examine how the actual old paths have been pushed aside, forgotten, marginalized, and labeled as nothing more than the unexciting theologizing of men who don’t have “the touch of God.”

First, I want it to be clear. I am for the old paths… as long as what we mean by “old paths” are the actual old paths — the doctrines and practices of the Bible and the teaching/preaching exhibited therein.

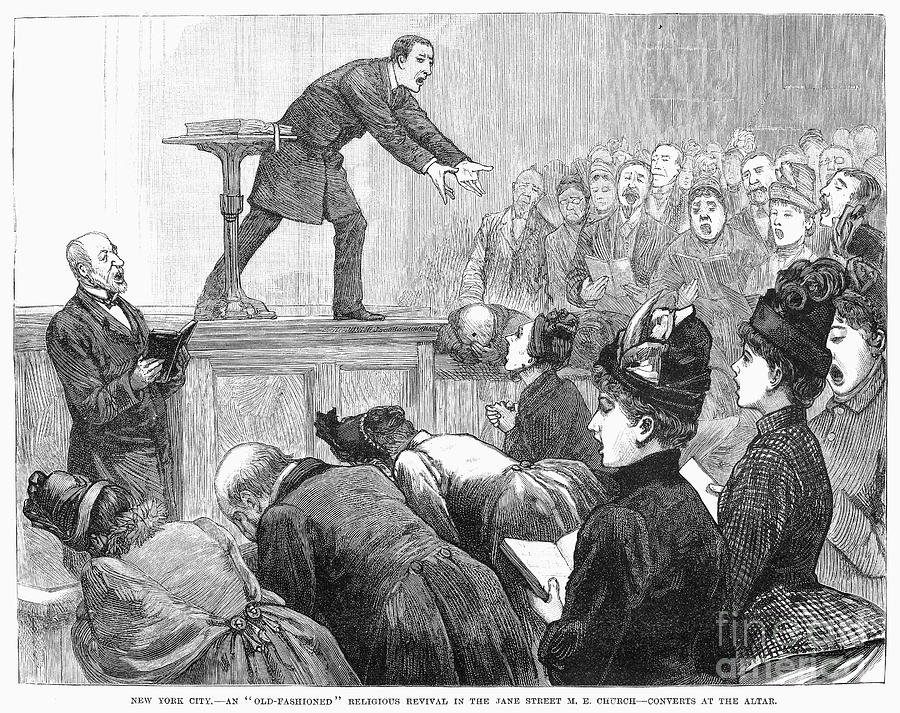

In the 1800s, Charles G. Finney, regarded by many as “the father of American evangelical pragmatism,” displayed his new measures as a departure from the Protestant and Anglican decorum that early America was accustomed to. These Protestant, as well as Anglican, congregations sat pensively in Catholic-esque worship while Finney’s new measures drew large, enthusiastic crowds. Perhaps he was trying to recreate the “old lights” versus “new lights” dynamic under Jonathan Edwards or the appeal of George Whitefield. Either way, I think he was trying to keep something going that was tapering off, namely the prior Great Awakening, and ended up forcing it.

Many rather enjoyed the shock and awe of a preacher being colloquial and irreverent. It was entertaining if nothing else.

But behind the scenes in churches we don’t really ever hear about, authentic church was happening. While the Second Great Awakening was really presented as a solution to the blight caused by public debauchery and drunkenness, authentic churches we probably won’t know about until Heaven were living the revived life as a pattern… all without the hoopla.

As a side note, I differentiate between Protestants and Anglicans because, while they had both been in Catholicism, they departed it for different reasons — the former theological and the latter political. Those are the differences between the Protestant and English Reformations, respectively. Arguably, Anglicanism never ceased being Catholic theologically. And Protestantism didn’t protest enough things.

As with many methodologies, they have a root in doctrinal collapse.

You can see by Finney's own statements how a false doctrine ultimately could lead to his methods:

"Moral depravity is not then to be accounted for by ascribing it to a nature or constitution sinful in itself. To talk of a sinful nature, or sinful constitution, in the sense of physical sinfulness, is to ascribe sinfulness to the Creator, who is the author of nature. . . . What ground is there for the assertion that Adam’s nature became in itself sinful by the fall? This is a groundless, not to say ridiculous, assumption, and an absurdity. . . . This doctrine is . . . an abomination alike to God and the human intellect." Finney’s Systematic Theology, Charles Finney. Pgs. 249-250, 261-263.

This is only one of many heresies Finney espoused. This denial of the inherent sin nature in man consequently suggests that man has some spark of good in himself with which he can turn to God apart from the Holy Spirit's work, thus resulting in a methodology that thinks a man can turn to God with nothing more than strong persuasion by a skilled orator. This is of course, the old Pelagian heresy.

And this is perhaps one of the largest matters of cognitive dissonance in Baptist churches today. We believe the Holy Spirit must lead the sinner to faith, then we proceed to lift up men who are the most enthusiastic and exciting orators as the best evangelists. Which is it then? Is it the Gospel message itself that is the power of God unto salvation, or the skill and style of the man who presents it? Often, we Baptists assert the former, but then conduct ministry by the latter.

Finney once wrote “A revival is not a miracle, nor dependent on a miracle, in any sense. It is a purely philosophical result of the right use of the constituted means — as much so as any other effect produced by the application of means.” (Finney, Lectures on Revivals of Religion)

This is a another way of saying that God’s work is nothing more than a numbers game subject to the law of averages. This is of course patently false and foolish. Again, I don’t know of any Fundamentalist who would agree with Finney on that, but their practice says otherwise.

According to one source, Finney “taught a second blessing type of experience whereby the believer achieved a new level of holiness and gained power for evangelism and preaching.” And that it was "an experience to be sought" (Cloud. History of the Churches, Vol. 2, p. 346). This paved the way for the amped up preaching that uses an ever increasing cadence and then crescendos with people shouting and wailing. Then they conclude from that experience that “God is moving.”

Some of this mindset would later be drawn into Fundamentalism along with Finney’s unwise consequentialist ministry ethics (i.e. pragmatism). The “new measures” would thrive as a result. Over time, Finney’s revival methods from his weeks long meetings simply replaced the Sunday service structure at most churches. His methods would later influence D.L. Moody, Billy Sunday, Gypsy Smith, J. Frank Norris, and many more. But one man in particular, the famed Billy Graham, would (through his early connection with John R. Rice and The Sword of the Lord publication) make Finney’s methods mainstream particularly in Baptist churches across America. This would result in an entire generations growing up in Finney-style church thinking that’s just the way it’s always been. One writer said:

“By the end of World War Two, in thousands of conservative Protestant churches, the only real difference between a revival meeting and Sunday worship was when they occurred.”

The bait-and-switch was complete.

Graham would eventually take pragmatism to its logical outcome, and Rice would separate with him over it. But toying with pragmatism in Finney-esque fashion in Baptist churches was here to stay and has never really left the Sword publication to the present, nor the churches in which the publication is lauded. John R. Rice was openly an “in essentials unity, in non-essentials liberty” man. That was the essence of Fundamentalism from its inception. It’s even in the name — only the Fundamentals were needed for fellowship. Though the “in essentials…” phrase is much less popular now, it is no less practiced in Fundamentalism. The combination of limited points of agreement and preaching that is more entertaining than it is deep, became a hot selling combination. And they’re still selling it.

In recent decades, through the Sword publication, men like Larry Brown, Jack Hyles, Jim Vineyard, and many more carried (sometimes unwittingly) the Finney revivalism banner, somehow along the way being convinced that their methods are old paths and represented in the pages of Scripture. In only 150-175 years, the old paths were invented, adopted, and universally accepted among Fundamentalists as being so old that they are assumed to be in the Bible. This is what a lack of discernment does.

Finney’s method of trusting the arm of flesh for your ministry became the philosophy du jour, and yet few knew that’s what they were doing.

In the third and final part of this series, we will see how Finney’s new measures, now called “the old paths,” persists today in more modernist groups.

Thomas Balzamo

Thomas Balzamo is the pastor of Colonial Baptist Church in Bozrah, Connecticut, host of the Reason Together Podcast, and associate editor of ReasonTogether.fm.

You can read more of Thomas’s writing on his personal site, ThomasBalzamo.com